| NSPM in English | |||

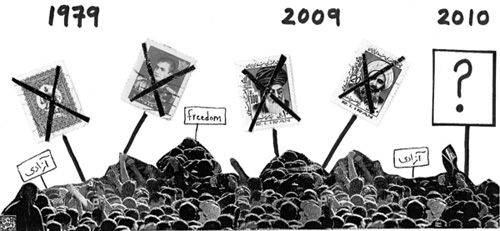

Another Iranian Revolution? Not Likely |

|

|

|

| петак, 08. јануар 2010. | |

|

(The New York Times, January 5, 2010) THE Islamic Republic of Iran is not about to implode. Nevertheless, the misguided idea that it may do so is becoming enshrined as conventional wisdom in Washington.

For President Obama, this misconception provides a bit of cover; it helps obscure his failure to follow up on his campaign promises about engaging Iran with any serious, strategically grounded proposals. Meanwhile, those who have never supported diplomatic engagement with Iran are now pushing the idea that the Tehran government might collapse to support their arguments for military strikes against Iranian nuclear targets and adopting “regime change” as the ultimate goal of America’s Iran policy. Let’s start with the most recent events. On Dec. 27, large crowds poured into the streets of cities across Iran to commemorate the Shiite holy day of Ashura; this coincided with mourning observances for a revered cleric, Grand Ayatollah Hossein Ali Montazeri, who had died a week earlier. Protesters used the occasion to gather in Tehran and elsewhere, setting off clashes with security forces. Important events, no doubt. But assertions that the Islamic Republic is now imploding in the fashion of the shah’s regime in 1979 do not hold up to even the most minimal scrutiny. Antigovernment Iranian Web sites claim there were “tens of thousands” of Ashura protesters; others in Iran say there were 2,000 to 4,000. Whichever estimate is more accurate, one thing we do know is that much of Iranian society was upset by the protesters using a sacred day to make a political statement. Vastly more Iranians took to the streets on Dec. 30, in demonstrations organized by the government to show support for the Islamic Republic (one Web site that opposed President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s re-election in June estimated the crowds at one million people). Photographs and video clips lend considerable plausibility to this estimate — meaning this was possibly the largest crowd in the streets of Tehran since Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s funeral in 1989. In its wake, even President Ahmadinejad’s principal challenger in last June’s presidential election, Mir Hossein Mousavi, felt compelled to acknowledge the “unacceptable radicalism” of some Ashura protesters. The focus in the West on the antigovernment demonstrations has blinded many to an inconvenient but inescapable truth: the Iranians who used Ashura to make a political protest do not represent anything close to a majority. Those who talk so confidently about an “opposition” in Iran as the vanguard for a new revolution should be made to answer three tough questions: First, what does this opposition want? Second, who leads it? Third, through what process will this opposition displace the government in Tehran? In the case of the 1979 revolutionaries, the answers to these questions were clear. They wanted to oust the American-backed regime of Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi and to replace it with an Islamic republic. Everyone knew who led the revolution: Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, who despite living in exile in Paris could mobilize huge crowds in Iran simply by sending cassette tapes into the country. While supporters disagreed about the revolution’s long-term agenda, Khomeini’s ideas were well known from his writings and public statements. After the shah’s departure, Khomeini returned to Iran with a draft constitution for the new political order in hand. As a result, the basic structure of the Islamic Republic was set up remarkably quickly. Beyond expressing inchoate discontent, what does the current “opposition” want? It is no longer championing Mr. Mousavi’s presidential candidacy; Mr. Mousavi himself has now redefined his agenda as “national reconciliation.” Some protesters seem to want expanded personal freedoms and interaction with the rest of the world, but have no comprehensive agenda. Others — who have received considerable Western press coverage — have taken to calling for the Islamic Republic’s replacement with an (ostensibly secular) “Iranian Republic.” But University of Maryland polling after the election and popular reaction to the Ashura protests suggest that most Iranians are unmoved, if not repelled, by calls for the Islamic Republic’s abolition. With Mr. Mousavi increasingly marginalized, who else might lead this supposed revolution? Surely not Ali Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, the former president who became a leading figure in the protests after last summer’s election. Yes, he is an accomplished political actor, is considered a “founding father” of the state and heads the Assembly of Experts, a body that can replace the Islamic Republic’s supreme leader. But Mr. Rafsanjani lost his 2005 bid to regain the presidency in a landslide to Mr. Ahmadinejad, and has shown no inclination to spur the masses to bring down the system he helped create. Nor will Mohammad Khatami, the reformist elected president in 1997, lead the charge; in 1999, at the height of his popularity, he publicly disowned widespread student demonstrations protesting the closing of a newspaper that had supported his administration. Many of the Westerners who see the opposition displacing the Islamic Republic emphasize the potential for unrest during Shiite mourning rituals, which take place at three-, seven- and 40-day intervals after a person’s death. During the final months of the shah’s rule, his opponents used mourning rituals held for demonstrators killed by security forces to catalyze further protests. But does this mean that a steady stream of mourning rituals for fallen protesters today will set off a similarly escalating spiral of protests, eventually sweeping away Iran’s political order? That is highly unlikely. First, Ayatollah Montazeri had unique standing in the Islamic Republic’s history; it is not surprising that the coincidence of his seven-day observance with the Ashura observation would have drawn crowds. His 40-day observance — which will fall on Jan. 29 — and the early February commemoration of the 1979 revolution might also encourage public activism. But there is nothing in the Islamic Republic’s history to support projections that future mourning rituals for those killed in the Ashura protests will elicit similar attention. For example, in late 1998 four prominent intellectuals were assassinated, allegedly by state intelligence officers, prompting considerable public outrage. Yet the mourning rituals for the victims did not prompt large-scale protests. In 1999, nationwide student protests were violently suppressed, with at least five people killed and 1,200 detained. Once again, though, the mourning dates for those who died did not generate significant new demonstrations. Likewise, after the presidential election in June, none of the deaths associated with security force action — even that of Neda Agha-Soltan, the young woman whose murder became a cause célèbre of the YouTube age — resulted in further unrest. In keeping with this pattern, the seven-day mourning observances for those killed in the Ashura protests generated no significant demonstrations in Iran. Clearly, comparisons of the Ashura protests to the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989, projecting a cascade of monumental consequences to follow, are fanciful. The Islamic Republic will continue to be Iran’s government. And, even if there were changes in some top leadership positions — such as the replacement of Mr. Ahmadinejad as president by Ali Larijani, the speaker of the Parliament, as some Westerners speculate — this would not fundamentally change Iran’s approach on regional politics, its nuclear program and other matters of concern. The Obama administration’s half-hearted efforts at diplomacy with Tehran have given engagement a bad name. As a result, support for more coercive options is building across the American political spectrum. The president will do a real disservice to American interests if he waits in vain for Iranian political dynamics to “solve” the problems with his Iran policy. As a model, the president would do well to look to China. Since President Richard Nixon’s opening there (which took place amid the Cultural Revolution), successive American administrations have been wise enough not to let political conflict — whether among the ruling elite or between the state and the public, as in the Tiananmen Square protests and ethnic separatism in Xinjiang — divert Washington from sustained, strategic engagement with Beijing. President Obama needs to begin displaying similar statesmanship in his approach to Iran. Flynt Leverett directs the New America Foundation’s Iran Initiative and is a professor of international affairs at PennsylvaniaStateUniversity. Hillary Mann Leverett heads a political risk consultancy. They publish the Web site The Race for Iran. http://www.nytimes.com/2010/01/06/opinion/06leverett.html?ref=opinion |

Од истог аутора

Остали чланци у рубрици

- Playing With Fire in Ukraine

- Kosovo as a res extra commercium and the alchemy of colonization

- The Balkans XX years after NATO aggression: the case of the Republic of Srpska – past, present and future

- Из архиве - Remarks Before the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament

- Dysfunction in the Balkans - Can the Post-Yugoslav Settlement Survive?

- Serbia’s latest would-be savior is a modernizer, a strongman - or both

- Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault

- The Ghosts of World War I Circle over Ukraine

- Nato's action plan in Ukraine is right out of Dr Strangelove

- Why Yanukovych Said No to Europe

.jpg)