| NSPM in English | |||

Dysfunction in the Balkans - Can the Post-Yugoslav Settlement Survive? |

|

|

|

| četvrtak, 22. decembar 2016. | |

|

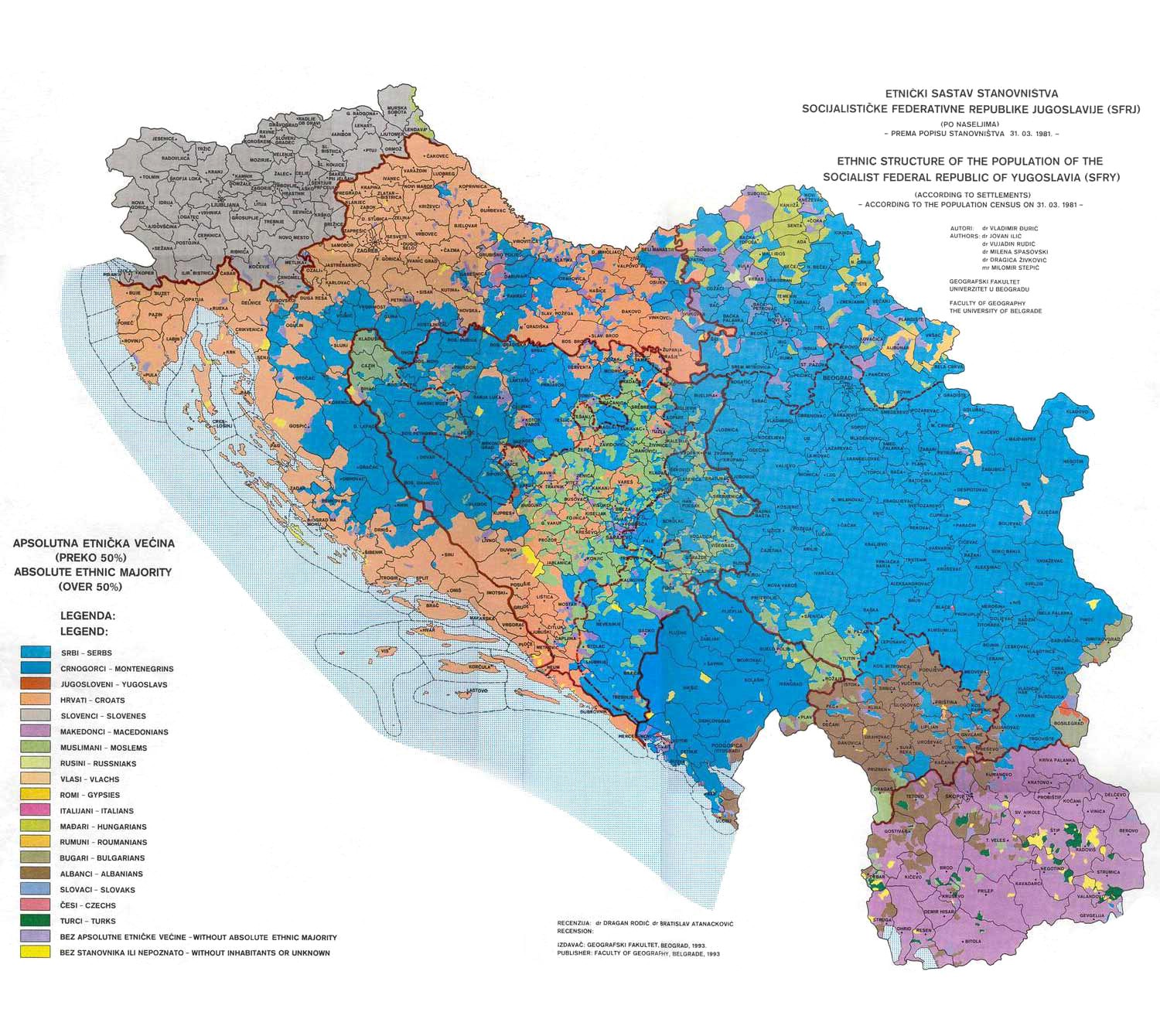

It is easy to dismiss all this as simply sound and fury, whipped up by opportunistic politicians. But it would be a mistake to ignore the will of the electorates, which have persistently shown their dissatisfaction with the multiethnic status quo and are demanding change. The choice facing Western policymakers is either to recognize the legitimacy of these demands and radically change their approach or to continue with the current policy and risk renewed conflict. A beautiful idea When Yugoslavia collapsed at the start of 1990s, there was nothing predetermined about what followed. One possibility was the emergence of nation-states, comparable to those elsewhere in Europe; another was multiethnic states based on internal administrative boundaries. In the end, the West determined the nature of the post-Yugoslav settlement by recognizing the independence of the old Yugoslav republics within their existing borders. In doing so, they were guided not only by a belief that this would promote justice and security but also by an ideological conviction that nationalism was the source of instability in Europe. Multiethnicity was seen as a viable, even desirable, organizing principle.

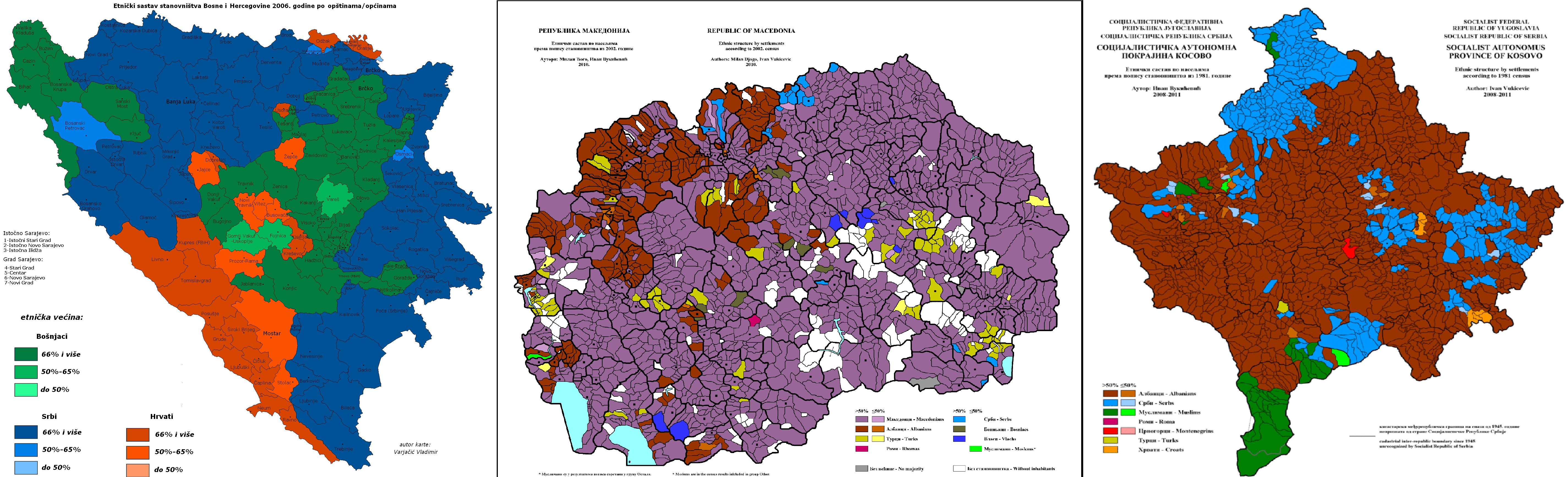

Unfortunately, this decision cut across the most basic interests of the emerging minority groups, which saw themselves condemned to second-class status in someone else’s state. In the 1990s, many took up arms to try to secure formal separation. Subsequently, wherever this failed, minorities have struggled to secure as much autonomy as possible within their adoptive states. Given the resistance of majority groups to the fragmentation of their polities, these attempts at separation have built tension into the very nervous system of the region’s various multiethnic states. As a result, the West has been compelled for the last two decades to enforce the settlement it imposed on the former Yugoslavia, deploying UN-run civilian missions and NATO troops as regional policemen. At first, Washington took the lead, but after the United States downgraded its presence in the Balkans over the last decade, primary responsibility for upholding the post-Yugoslav settlement passed to the European Union. In doing so, the EU substituted the hard power of the U.S. military for the soft power of enlargement. Its assumption was that the very act of preparing for EU membership would transform poor authoritarian states into the kinds of prosperous, democratic, law-bound polities in which disaffected minorities would be content to live. For a short while toward the end of the last decade, the policy appeared to be working. However, the disquiet of minorities eventually made it clear that the EU’s approach could not resolve the problems created by multiethnicity. Its central misconception was that minorities would give higher priority to political and economic reform than to grievances about territory and security, which would no longer matter after joining the EU. All this made sense to Europeans living in their post-historical paradise but did not hold water for minorities situated in the Hobbesian realm of the Balkans, unable to secure even their most primary needs—their security, rights, and prosperity. Instead, issues of governance and the economy, and even more peripheral concerns such as education and the environment, were pushed to the margins as political institutions became gridlocked by intractable questions about territory, identity, and the balance between central and regional power. Day-to-day, Bosnia, Kosovo, and Macedonia were mired in political dysfunction, economic stagnation, and institutional corruption, even as their more homogenous neighbors, such as Albania, Croatia, and even Serbia, began to prosper. The policy is further complicated by the Euroskepticism now sweeping across Europe, which threatens any remaining hope that integration could lead to stabilization. A Eurobarometer poll last year suggested that only 39 percent of EU citizens favor enlargement and 49 percent oppose it. Earlier this year, voters in the Netherlands decided in a referendum to block Ukraine’s integration with the EU; it was, in effect, a vote against enlargement. Previous governments in both Austria and France have also pledged to condition future enlargement upon a national referendum. As a result, the process of enlargement has stalled. Thirteen years after its launch at a summit in Thessaloniki, four of the six non-EU states in the region have yet to open negotiations on EU membership. Serbia has only tentatively begun, and Montenegro, the region’s most advanced state, has only provisionally closed two of the 35 negotiating chapters, four years after starting. (By contrast, the central European countries completed the entire negotiating process within the same time frame.)

To complicate matters, Russia is using its influence to frustrate the process of integration, encouraging unhappy minorities such as the Bosnian Serbs to escalate their demands for separatism and threatening the pro-integration government in Montenegro. Turkey is nurturing the support of disaffected Muslims such as Bosniaks and Macedonian Albanians. And China is enthusiastically providing governments across the region with no-strings funding for investment in infrastructure, undermining the West’s attempts to promote conditions-based internal reform. The debate on the Balkans has been dominated for far too long by Western diplomats and academics who deny what is obvious to almost everyone on the ground: that multiethnicity in the region is a beautiful idea and a miserable reality. Almost every state has recently experienced serious unrest as people lose faith in the power of the EU to deliver them from their current state of hopelessness, poverty, and corruption. Adding to these tensions, minorities are trying to take control of their destiny by demanding the right to a separate territory in countries where the central government inevitably prioritizes the interests of the majority group. This combination of factors is already destabilizing the Balkans and, in turn, threatening to undermine the post-Yugoslav settlement. For the moment, the EU’s ability to preserve the status quo in the Balkans is not completely spent because of its collective veto on border changes in the region. Meanwhile, Brussels is continuing to squeeze every last bit of leverage out of its policy of integration. In the last couple of years, it has pushed all the region’s laggards—Albania, Bosnia, and Kosovo—one step closer to membership. But the EU is still struggling mightily to impose its authority. European diplomats were unable to resolve a two-year political crisis in Macedonia that began when the governing parties, which just won early elections, were implicated in wiretapped recordings revealing gross corruption and outright criminality. The EU also failed to conclude an agreement to normalize relations between Serbia and Kosovo. (In fact, relations between the two governments are deteriorating.) Perhaps most serious, Bosnia’s Republika Srpska proceeded with a controversial referendum in October, despite EU protestations, about retaining its national day holiday, which Bosnia’s highest court found discriminatory against non-Serbs and which Western diplomats said violated the Dayton constitution that holds Bosnia together. The EU’s subsequent inability to punish Bosnian Serb leaders through sanctions could embolden them to organize an independence referendum. A miserable reality What happens next, of course, is a matter of speculation. In all probability, the post-Yugoslav settlement will continue to hold in law. But separatist groups can easily gain a kind of functional independence by repudiating the authority of the central government and then waiting for more opportune circumstances, such as the collapse of the EU, to formalize this separation. Left unchecked, the situation risks sliding toward renewed conflict as majority populations fight to maintain the integrity of their states.

If this is the danger, then how should policymakers respond? The key consideration is that the existing policy of stabilization through integration, to the extent that it ever worked, has fully run its course, given the effective end of EU enlargement. By laboring onward with an obsolete policy that relies on an elusive reward, and without any sanctions for noncompliance, the West is handing the power of initiative to local revisionists and their external sponsors, Russia and Turkey, which are pursuing self-interested policies that cut across the West’s objectives. Some argue that the existing policy could be made to work if only Brussels tried a bit harder, backing up its pledge of EU membership with greater efforts to promote regional cooperation, democracy, transparency, economic development, and so on. However, this is wishful thinking. The promise of EU membership is broken, and every one of these initiatives has been tried in spades for the last 20 years. Others, especially majority groups on the ground, argue that Europe should get tough with politicians who advocate separatism, as Washington did in the past. This might work if Europe were willing to intervene in the region indefinitely. But the political context has changed radically over the last decade. No one wants another civilian mission, and threatening a group such as the Bosnian Serbs would simply drive it into Russia’s open arms. A radical new approach is therefore required that forges a durable peace by addressing the underlying source of instability in the Balkans: the mismatch of political and national boundaries. The two-decade experiment in multiethnicity has failed. If the West is to stay true to its long-standing goal of preserving peace in the Balkans, then the moment has come to put pragmatism before idealism and plan for a graduated transition to properly constituted nation-states whose populations can satisfy their most basic political interests. Given the divisions in Europe, the United States needs to step up and take control of the process. In the short term, Washington should support the internal fragmentation of multiethnic states where minorities demand it—for example, by accepting the Albanians’ bid for the federalization of Macedonia and the Croats’ demand for a third entity in Bosnia. In the medium term, the United States should allow these various territories to form close political and economic links with their larger neighbors, such as allowing dual citizenship and establishing shared institutions, while formally remaining a part of their existing state. In the final phase, these territories could break from their existing states and unite with their mother country, perhaps initially as autonomous regions. A Croat entity in Bosnia would merge with Croatia; Republika Srpska and the north of Kosovo with Serbia; and the Presevo Valley, western Macedonia, and most of Kosovo with Albania. Meanwhile, Montenegro, which may lose its small Albanian enclaves, could either stay independent or coalesce with an expanded Serbia. In pursuing this plan, the United States would not be breaking new ground but simply reviving the Wilsonian vision of a Europe comprising self-governing nations—but for the one part of the continent where this vision has never been applied. Inevitably, there would be difficulties and risks, although not as serious as those inherent in the existing failed policy approach. Serbia would have to let go of Kosovo, minus the north, but the compensation would be the realization of a Serbian nation-state in the territory where Serbs predominate. Albanians would similarly have to give up northern Kosovo. More problematic, Bosniaks and Macedonians would need to accept the loss of territory to which they are sentimentally attached and without any significant territorial compensation. In truth, this would simply be a formalization of the existing reality. But the United States and Europe would need to smooth the transition by investing heavily in their economic development and by involving a range of international partners—including Turkey, Russia, and the key regional states of Albania, Croatia, and Serbia—to commit to their security. During a transitional period, Washington and others may also have to deploy peacekeepers to uphold the borders of the expanded Albanian, Croatian, and Serbian states. But this would be only a temporary commitment, in contrast with the current deployment needed to uphold an illegitimate status quo—4,300 troops in Kosovo, including around 600 from the United States, and another 600 troops in Bosnia. Ultimately, it is easier to enforce a separation than a reluctant cohabitation. These suggestions may shock those who are heavily invested in the current policy of multiethnicity. But the debate on the Balkans has been dominated for far too long by Western diplomats and academics who deny what is obvious to almost everyone on the ground: that multiethnicity in the region is a beautiful idea and a miserable reality. There is no question that undoing the existing settlement would be complicated. However, a managed process of separating groups with divergent national interests, rather than forcible coexistence for the sake of an abstract ideological goal, would eliminate the most serious risk facing the region—namely, uncontrolled disintegration and renewed conflict. It would also give places such as Bosnia and Kosovo a better chance of developing in the longer term. This is eminently preferable to the status quo. After many wasted years, the West must have the confidence to embrace a new approach that cuts through hardened assumptions. For the new administration, there is now an unprecedented opportunity to rethink a policy that has been flawed since its very inception. In a final act of service to the Balkans, the United States should finish the job it started so long ago, this time once and for all. |

Od istog autora

Ostali članci u rubrici

- Playing With Fire in Ukraine

- Kosovo as a res extra commercium and the alchemy of colonization

- The Balkans XX years after NATO aggression: the case of the Republic of Srpska – past, present and future

- Iz arhive - Remarks Before the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament

- Serbia’s latest would-be savior is a modernizer, a strongman - or both

- Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault

- The Ghosts of World War I Circle over Ukraine

- Nato's action plan in Ukraine is right out of Dr Strangelove

- Why Yanukovych Said No to Europe

- Bosnia and Syria: Intervention Then and Now

.jpg)

The political settlement in the former Yugoslavia is unraveling. In Bosnia, the weakest state in the region, both Serbs and Croats are mounting a concerted challenge to the Dayton peace accords, the delicate set of compromises that hold the country together. In Macedonia, political figures from the large Albanian minority are calling for the federalization of the state along ethnic lines. In Kosovo, the Serb minority is insisting on the creation of a network of self-governing enclaves with effective independence from the central government. In Serbia’s Presevo Valley, Albanians are agitating for greater autonomy. In Montenegro, Albanians have demanded a self-governing entity. And in Kosovo and Albania, where Albanians have their independence, nationalists are pushing for a unified Albanian state.

The political settlement in the former Yugoslavia is unraveling. In Bosnia, the weakest state in the region, both Serbs and Croats are mounting a concerted challenge to the Dayton peace accords, the delicate set of compromises that hold the country together. In Macedonia, political figures from the large Albanian minority are calling for the federalization of the state along ethnic lines. In Kosovo, the Serb minority is insisting on the creation of a network of self-governing enclaves with effective independence from the central government. In Serbia’s Presevo Valley, Albanians are agitating for greater autonomy. In Montenegro, Albanians have demanded a self-governing entity. And in Kosovo and Albania, where Albanians have their independence, nationalists are pushing for a unified Albanian state.