| NSPM in English | |||

Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan: A Customs Deal and a Way Forward for Moscow |

|

|

|

| понедељак, 04. јануар 2010. | |

|

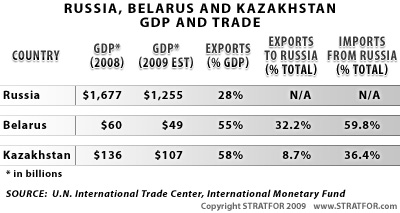

(Stratfor Today, December 31, 2009) A customs union between Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan is set to go into effect on Jan. 1, 2010. The long-awaited union will completely do away with customs duties between the three former Soviet states and also will impose a common external tariff system, applicable to thousands of goods, between Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan and the rest of the world. While the official details of the customs union have yet to be decided on and will only be solidified in multiple phases over the next year, it is clear that the integration between the three countries will allow Russia to further entrench its economic influence over Belarus and Kazakhstan. Indeed, the union may be just the start of a larger and deeper integration between the countries across all spheres. Economic activity between Russia, Belarus, and Kazakhstan already is quite profuse. The three countries maintain substantial links and are structurally integrated in such key sectors as manufacturing, energy, and agriculture, among others. This is due not only to the proximity of the three countries but also to the fact that their current borders were nonexistent during the days of the Soviet Union. Much of the infrastructure and industry — explicitly designed to integrate the republics with one another — remains essentially in place and unchanged to this day. This has fostered a strong trade and investment relationship between the three countries, with Russia serving as the primary exporter of goods to Belarus and Kazakhstan as well as one of the leading destinations for their exports.

But while the three countries maintained a de facto free-trade zone following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, after the fall each country adopted separate economic policies and legal infrastructure, with the establishment of three independent central banks, monetary systems and tariff regimes. They also were free to establish trade relationships with foreign entities irrespective of the exporting interests of their former Soviet partners. Part of this is set to change when the customs union enters into force. The three countries have decided to take a gradual approach in formalizing the tariff rates. The customs union is set to be implemented in multiple phases, beginning with the launch of common customs duties on Jan. 1, followed by a common customs code on July 1, and then another, yet to-be-determined consolidation on Jan. 1, 2011. Between these intervals, each state will have a chance to pause and evaluate the effects of the new agreements, as they have yet to be cemented even by the government officials who are overseeing them. This has already been alluded to by Kazakh Deputy Prime Minister Umirzak Shukeyev’s request for extra time to discuss tariffs on goods including petrochemicals, pharmaceuticals, and agricultural produce, as well as both Belarus and Kazakhstan issuing a list of “sensitive commodities” to which they will have veto power on changes to their customs duties. But what is known is that the integration of external tariffs basically will involve Belarus and Kazakhstan raising their tariff rates to be essentially the equivalent of Russia’s: It is estimated that more than 90 percent of the new customs regime will be based on Russia’s current duties. The economies of Belarus and Russia both are dependent on heavy industry and manufacturing, so both countries keep their tariffs generally high in order to protect these industries (although Belarus, as a smaller economy with less manufacturing capacity, has in most cases slightly lower tariffs than Russia). Kazakhstan’s economy, however, is heavily dependent on oil revenue and has relatively little industrial production, and as a result has much lower tariffs. Belarus will therefore have to raise tariffs on only a few dozen items, while Kazakhstan will have to raise rates on an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 items. Raising rates would make imports to Belarus and Kazakhstan more expensive and would thus make the two countries much more reliant on imports from Russia, whose exports would become more attractive within the customs union. That Minsk and Astana would willingly allow their imports to become more expensive and venture into a customs union is due to the fact that the economic recession in Belarus and especially Kazakhstan has left the countries looking for economic stability wherever they can find it, and Russia’s growing economic influence in the region makes it the most applicable suitor. The convergence of tariffs likely will only be the beginning of a more widespread economic integration between the countries, however, as Russian President Dmitri Medvedev, Belarusian President Aleksandr Lukashenko and Kazakh President Nursultan Nazarbayev recently declared their intention to create a “single economic space” by Jan. 1, 2012. This envisions using the customs union to pave the way for other means of streamlining the economic systems of Belarus and Kazakhstan with that of Russia, as can be seen by Belarusian Vice Premier Andrei Kobyakov advocating Dec. 29 that the National Bank of Belarus should reduce its interest rates to coordinate its policy with the Central Bank of Russia. Other former Soviet countries — Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan and Armenia — have also indicated their willingness and enthusiasm to join the customs union and eventually the single economic space. While these represent relatively tiny economies which already are dominated by Moscow, a notable development occurred when Viktor Yanukovich, the frontrunner in Ukraine’s presidential elections, stated that he endorses the customs union and will initiate Ukraine’s accession if he is elected president. If Ukraine, which has a relatively large consumer market, raised its tariffs to match those of Russia, Ukraine likely would increase its imports from Russia, and thus its general economic dependence on Moscow, by a considerable margin. To Russia, the customs union with Belarus and Kazakhstan is just the first step to a more comprehensive integration between the three countries, one that goes beyond the economic realm into a deeper political union. It is only natural for Moscow to target these countries first, as these were two of the former republics that were least enthusiastic about the break-up of the Soviet Union. The next step involves more challenging goals, such as the economic and political re-integration of Ukraine, Georgia, the Baltics and Central Asia. The upcoming debut of the customs union, therefore, is not just about Russia exerting its influence in Belarus and Kazakhstan but about Moscow’s attempt to formalize its authority in these countries and lay the groundwork for bolder moves throughout the rest of its periphery in 2010 and beyond. |

Од истог аутора

- The Nabucco West Project Comes to an End

- Remaking the Eurozone in a German Image

- Serbia: A Weimar Republic?

- NATO's Lack of a Strategic Concept

- Surveying Turkish Influence in the Western Balkans

- The Geopolitics of Turkey: Searching for More

- Kosovo – Consequences of the ICJ Opinion

- Kyrgyzstan and the Russian Resurgence

- Montenegro's Membership in NATO and Serbia's Position

- ЕУ: Убрзано ширење на Балкан

- The Return of Germany

Остали чланци у рубрици

- Playing With Fire in Ukraine

- Kosovo as a res extra commercium and the alchemy of colonization

- The Balkans XX years after NATO aggression: the case of the Republic of Srpska – past, present and future

- Из архиве - Remarks Before the Foreign Affairs Committee of the European Parliament

- Dysfunction in the Balkans - Can the Post-Yugoslav Settlement Survive?

- Serbia’s latest would-be savior is a modernizer, a strongman - or both

- Why the Ukraine Crisis Is the West’s Fault

- The Ghosts of World War I Circle over Ukraine

- Nato's action plan in Ukraine is right out of Dr Strangelove

- Why Yanukovych Said No to Europe

.jpg)